Nate Norman, Idaho Pizza Delivery boy turned into a Million Dollar Drug Kingpin, Kid Cannabis

Nate Norman was hanging out with his buddy Topher Clark when he came up with The Idea. The two friends were sitting around Nate’s house, a dumpy little place near the cemetery, and both of them were extremely stoned. And yet The Idea had more legs than your typical pot-inspired idea. It did not involve a second Twinkie inside the first one. It did not involve genetically modifying the bugs so their blood would not be blood but windshield-wiper fluid. It was, in fact, based on a practical application of global economic theory. That, and cheap weed in Canada.

At the time, Nate was a nineteen-year-old high school dropout who worked at a Pizza Hut in Coeur D’Alene — a gorgeous but dull resort town in Idaho — and sold the occasional dime bag on the side. Chubby and baby-faced, Nate had never been the type to come up with a million-dollar brainstorm. “He was one of those guys everybody used to pick on,” says his friend Scuzz — Ben Scozzaro, a year ahead of Nate at Coeur D’Alene High. “He looks like the Keebler Elf. That’s what we used to call him, actually.” Nor was Nate much of a scholar. His girlfriend Buffy once received a letter in which Nate spelled “pot” with an extra “t.” “He can’t spell ‘marijuana,’ either,” she adds.

Always ready with an eager grin, Nate developed a puppy-dog need for approval — and perpetually holding proved a quick way to earn the love, or at least tolerance, of his peers. Topher, nine years his senior, initially met Nate as a customer. An avid outdoorsman who hunted deer and elk for meat, Topher didn’t have much in common with Nate but found him goofy yet likable, a “fat, funny kid” with a “big heart.”

Nate had been getting his stash from a dealer in Spokane, Washington. But he had heard about how easy it was to cross the Canadian border — only an hour north of Coeur D’Alene — and bring back the popular, extremely potent marijuana growing in abundance in British Columbia and known, generically, as “B.C. Bud.” Rumor had it that the town of Nelson had become a sort of hippie Shangri-La, a place where if it took you more than ten minutes to find someone to sell you a dime bag, there was a good chance you were already high.

Nate turned to Topher and said, “I’m cool. Are you cool?”

Topher said, “I try to be.”

Nate said, “I’ve got a plan.”

The Idea turned out to be a textbook case of business economics: Buy low, sell high and eliminate the middleman. Things happened quickly after that. Suddenly, Nate and Topher and all of their friends had more cash than they’d ever dreamed of, along with expensive cars, hot girlfriends and fancy lakefront homes. And then, just as quickly, they began to lose control. Harder drugs, guns, paranoia, eventually violence — it was like a movie, everyone agrees. “Mini-Scarface,” chuckles Nate’s lawyer Frank Cikutovich.

“Have you seen Blow?” asks Topher. “You should sit down and watch it sometime. That’s what it was like. We’re at these parties, watching naked women jump into pools, feeding piranhas in aquariums, smoking out of big, fancy bongs.”

Topher is sitting, at the moment, in the visiting room of a federal prison in Terminal Island, California. He’s a big guy, with solid arms and blocky features. Outside, there are palm trees in the parking lot and a decent view of the harbor. “When I heard about the Butler kid, I just wanted out,” he says. He attempts a smile, but his eyes do not cooperate, the final effect being more of a pained wince. “I was like, this is pot, right?’ This isn’t supposed to happen. No one’s supposed to die.”

According to law-enforcement officials, the sale of B.C. Bud has become a $7 billion-a-year industry. Though marijuana remains illegal in Canada, the stance of the government regarding pot is far less hysterical than in the United States, with laws enforced sporadically and penalties never especially stringent. “Americans like to think they can stop this,” says Donald Skogstad, a defense lawyer in British Columbia who specializes in pot cases. “The Canadian border is five times longer than the Mexican border. There is no fence, no barrier at all, just a curtain of trees. Right now, they’re catching all the dumb people. That’s all the Americans get. They’ll never get you if you’re doing it properly.”

Smugglers have buried stashes in semi trucks filled with wood chips and driven across the border. They have hidden pot in buses, in horse trailers, on trains and in mobile homes driven by gray-haired retirees. They speed across the border on snowmobiles. They kayak backwoods rivers, or fill the fiberglass hulls of yachts and sail down. They fly small planes, low, dropping their loads at agreed-upon locales — farms, raspberry fields — without landing. They have dug a 360-foot tunnel, beginning in a Quonset hut in Canada and ending in the living room of a home in Lynden, Washington. They drag their stashes underwater, behind fishing boats, so the line can be cut if an agent approaches; buoys, attached to the loads with dissolvable strips of zinc, rise to the surface the following day. They float hollowed-out logs, outfitted with GPS tracking systems, down the Kettle River. And some — “the bravest,” says Skogstad, “but not necessarily the brightest” — hike the seven-mile border crossing, through the forest, on foot.

Once Nate hatched his smuggling plan, he and Topher realized that their first order of business would be to scrape together enough cash to make a buy. Luckily, Topher had salvaged a sunken jet boat from the lake in Coeur D’Alene and had spent the summer restoring it. To kick-start their enterprise, he dragged it to the side of the highway and sold it within minutes for $1,500.

The two friends both had big plans. Raised a Buddhist, Topher had essentially grown up on a boat, sailing the world with his free-spirit parents before they settled in Coeur D’Alene when he was fourteen. Though Topher dreamed of opening his own car-detailing shop, by the time he met Nate he was working part-time at an amusement park, living with his brother and barely scraping by.

Nate was also into cars. As a kid, he restored them with his grandfather, who became a father figure after his parents divorced and his mother moved the family to Idaho. The oldest of four children, Nate became especially protective of his mother. Despite his academic shortcomings, he was always a hard worker, his string of shitty day jobs including paper routes, telemarketing gigs and a stint at the Taco John at the mall.

“Nathaniel has always been a really good kid,” insists his mother, Teresia Franks. “He’d go out of his way to help somebody. There was an old lady who lived across the street from us. Her driveway would get blocked every time the snowplow would go by. Nathaniel would always run over and shovel her drive, and later she’d tell me that she tried to give him money and he’d say, ‘No, no.'”

For their first pot run, Nate and Topher drove up to Creston, B.C., a little farming town just over the border. Once there, they hit the local bars in search of a connection. It didn’t take long. “We saw this old man, and we made a hand gesture, like smoking a bowl,” Topher recalls. “He just nodded his head and told us to come outside.”

“You guys looking for weed?” the man asked.

The boys said yes.

“You Americans?” he asked.

The boys said yes.

“Good,” the man said.

Minutes later, they were in an apartment making their first deal: $1,400 for a pound of B.C. Bud. “I put it under my arm like a football,” Topher says.

Nate drove back across the border, while Topher, the designated runner, began the long hike through seven miles of thick forest. It was late afternoon. He’d changed into camouflage gear, stashing his street clothes and the pot in a backpack. It was a scary trip nonetheless. Topher was not only worried about border agents but also grizzly bears and mountain lions, and he wanted to reach U.S. territory before dark. He and Nate had bought two-way radios to arrange the pickup. They gave each other code names. Nate was Joe Blow. Topher was the Space Cowboy.

Once safely on American soil, the pair met their friends at an Outback Steakhouse and, in Topher’s words, “ate like starving coyotes.” Excited by the success of their first outing, they showed their friends the weed — which was, they all had to admit, fairly skunk-looking tourist weed. “B.C. Bud is really Chronic,” says Scuzz, who had been brought on board as a dealer. “This was like Cali Mexican weed.”

But the quality didn’t stop it from moving. Hitting the streets of Coeur D’Alene, Scuzz and the others sold it all in a couple of hours.

Having doubled their initial investment in roughly a day, Nate and Topher quickly planned a second run. This time, they bought two pounds. Before they knew it, they had gone from struggling to put gas in their cars to running a major pot enterprise that was bringing in thousands of dollars a day. “Within a few weeks I went from selling eighths to quarter pounds,” says Scuzz, who could pass for a pro snowboarder with his goatee and wraparound shades. “Our plan was to make 3 million and get out. When you crunch the numbers, that’s nothing. We figured out we could do it in fourteen months. But when you’re making twenty or thirty grand a week, why the fuck would you stop?”

As business boomed, the guys found a couple of steady suppliers from Nelson — a town that Drew Edwards, in his book West Coast Smoke, calls “the marijuana-culture capital of North America.” Nelson’s remoteness makes it ideal terrain for pot growers — so much so that the town of 10,000 has its own currency exchange.

Overlooking the main street is the Holy Smoke Culture Shop, a white clapboard house with a giant marijuana leaf painted on the side. Next to the pot leaf is a profile of Peter Tosh large enough to rival Soviet-era portraits of Stalin. Holy Smoke is the local head shop — but in Nelson, it functions more like a second city hall. Hikers, snowboarders and potheads come to Nelson from all over the continent to openly smoke weed and to buy one of the various strains of B.C. Bud, christened with brand names for marketing purposes: Triple-A, Crystal Globe, SIN/D.

“You know, name sells,” says Jonas, a local who has worked full-time as a grower and smuggler. “I read in People or some stupid shit a list of the highest-stress jobs. Number one was president of the United States. Number two was drug smuggler.” He chuckles. “This is above astronauts!”

To keep up with demand, Nate and Topher soon drew their friends into the operation. Aside from Scuzz, there was Topher’s friend Tim Hunt, a nineteen-year-old whose family had moved to Coeur D’Alene from Alaska after his father, caught poaching moose, committed suicide; Scuzz’s best friend, Rhett Mayer, a supersmart kid who never touched weed but began driving scout cars en route to the border; and Nate’s buddy Dustin Lauer, ironically nicknamed “the Rock” because he was five-foot-six and chubby but always tried to be a tough guy. The dealers rarely made border runs. “Nate did it a couple of times, just for fun,” says Topher. “He’d drink four Red Bulls and be darting from tree to tree like a crazy guy.”

Topher remained the head runner, paid a flat fee of $1,000 per crossing. He was also in charge of the new recruits. The crew was immediately outfitted with hundreds of dollars’ worth of equipment, everything from new boots to night-vision goggles to a spray, purchased on the Internet, that was supposed to make them “invisible” to heat sensors. (Says Terry Morgan, a police detective who investigated Nate’s crew, “I always tell people, ‘Oh, yeah, that works great. Keep using it.'”)

Runners would cross the border, six at a time, carrying long canvas hockey bags filled with cash — eventually as much as $400,000 a run. In Canada, they would meet their contacts from Nelson on an old closed road and exchange the cash for weed. They always crossed at night. Once they were back in America, a truck would swing by and pick up the weed. Topher and his men would spend the rest of the night in the woods and be picked up around sunrise. Aside from the obvious demands of hiking for miles with heavy loads, they had some close calls. One night, Topher stumbled across a DEA agent, asleep in his truck; another time, they got lost and nearly froze to death when the temperature dropped to fourteen below zero.

Nate and his friends were suddenly making — and spending — preposterous amounts of money. They bought four-wheelers, jet skis, plasma-screen televisions, minidisc players. “If it had a ‘best’ option, we had it,” says Scuzz. Tim Hunt threw a lavish New Year’s Eve lingerie party. Platinum jewelry, deemed not flashy enough, was returned for gold. Aside from Topher, everyone involved was in their teens and early twenties, which made the upswing in their collective lifestyle that much more radical.

“When we started, most of us were still living with our moms,” notes Scuzz. Now, they were buying or renting enormous lakefront homes — one simply as a stash house for money and drugs. Nate’s house had eight bedrooms. “I moved into a lake house that was unreal,” says Scuzz. “My parents didn’t know about it. I told them I lived in a bullshit-ass apartment.”

Perhaps unwisely, the guys flagrantly ignored an oft-quoted maxim from Scarface — namely, never get high on your own supply. “We were stoned every day,” Scuzz confirms. “Me and Nate would just take the best-looking bags. I don’t think I had a sober day for three years. I mean,” he quickly adds, “a lot of it was networking. We were finding clients. You know, go hang out at some dude’s house, smoke with him, find out if he knows anybody out of state to sell to. Next day, go to some other dude’s house. But in the in-between time, yeah, we’d be rolling two-ounce joints and playing video games.”

Such behavior, while enjoyable, led to the occasional lapse in judgment. Example: Nate decided he needed a Cadillac Escalade, so he sent a couple of his guys — with $40,000 in cash — to buy one from some dude in North Dakota.

“The dumb-asses,” says Detective Morgan, “took a video camera.”

“It’s like watching Wayne’s World,” says Cikutovich, Nate’s lawyer. “They’re videotaping themselves smoking doobies. Then they get there and there’s no Escalade, and they’re going, ‘Dude! Let’s find this guy and beat him up!'” Nate eventually bought the Escalade in Seattle, paying cash and telling the salesman he won the money gambling.

“We were doing a lot of stupid shit,” groans Scuzz. “I mean, we were living in a town where, if you get in a car wreck, your mom’s uncle will know immediately. Everyone knows everything that’s going on. And we’re moving hundreds of pounds of weight, making millions of dollars. But we were a bunch of eighteen-year-olds, and we weren’t thinking about the long run. We just had that attitude. We didn’t give a fuck.”

Nate, meanwhile, was beginning to change. His presence had always been tolerated with a smirk. Now, suddenly, he was Tony Montana. He became cocky and disrespectful. He also began using cocaine, which made him paranoid. They had all agreed, early on, not to have guns. But now, with so much cash around, Nate bought a Mac-10 9 mm submachine gun and an AR-15 assault rifle.

“He went from having this humble personality to thinking he was this badass smuggler no one could touch,” says Topher. “He would drive around town with his twenty-four-inch rims and diamond chains, listening to hardcore rap. Just this perfect drug-dealer image. And people were starting to fear him, because he had power and money.”

Now the only thing the drug kingpin formerly known as the Keebler Elf needed was a girlfriend. He found her, of course, at a strip club.

Stateline showgirls falls, technically, on the Idaho side of the border with Washington, in a town that’s actually called Stateline. As Idaho law does not permit nude dancing in establishments serving alcohol, half of Stateline Showgirls is a strip club, where you can buy a Coke and watch a topless girl gyrate to U2’s “With or Without You.” The bar is next door. It also has a stripper pole, and occasionally a fully clothed server wearing, say, jeans and a tight red sweater will perform a perfunctory pole dance.

Buffy (her stripper name; she was born Katrina Stewart) works several nights a week at Stateline Showgirls. She’s off tonight, drinking in the bar and wearing a low-cut blouse that could pass for a negligee. The top shows off her rather impressive cleavage, the surgical enhancement of which is a favorite topic of conversation with Buffy. She’s cute and blond, and began dating Nate Norman almost four years ago, when he was nineteen and she was twenty-six. “I met Nathan next door, down by the stage,” she says. “I remember he saw me and said ‘Fabulous.’ That’s my word! I always say that. I couldn’t believe a guy would say it to me. We did some dances after that, and became best friends. He had a great smile.” Buffy smiles herself. “That first time he walked in here, he looked, literally, like he was twelve.”

They soon became a couple. Buffy liked dating a younger guy with no baggage. Nate also lavished her with gifts. They took trips to Puerto Vallarta, Mexico. Buffy insists she had no idea of Nate’s true profession — “He told me he owned a snowplow business” — but she admits to being a longtime pothead. She once considered submitting a topless photograph of herself with a huge bud between her breasts to High Times. She used to refer to Spokane, where she lives, as “Spokompton” on bad days and “Spoke Vegas” on good ones. Now she simply refers to it as “Spokannabis.”

With a stripper girlfriend, weapons and gratuitous bling, Nate’s transformation was nearly complete. “Oh, man, you wouldn’t believe it,” says Scuzz. “He started buying these stupid homey clothes, when he’s a white dude from Coeur D’Alene. And he got this crazy idea in his head that he was going to be a rapper. He got this little accent when he talked, and he’d always be freestyling in the car. That’s why you couldn’t help but like him. He’d do such stupid shit.”

They all would. One night, during an especially crazy party at Tim Hunt’s — the place was completely packed out, at least 150 people, and everyone’s wasted — a fight broke out over a girl. One of the kids left and came back with a group of friends. They bum-rushed the house, knocking down the door and starting a full-on brawl. People were getting thrown over furniture and down the stairs. “If you saw someone you didn’t know,” says Scuzz, “you took a swing.” Tim ended up running outside with his .45 and shooting it in the air. But it was so loud in the house, with the music and the fighting, nobody heard him. So Nate, who was piss-drunk, grabbed another Magnum, only he shot it off in the house. “Have you ever shot a .45 Magnum in a house?” Scuzz asks. “It’s deafening. It was like a fucking bomb went off.” All the girls started screaming and everyone ran outside.

Scuzz and his girlfriend made it to their Lexus and took off, but they were immediately pulled over by five cops, who yanked Scuzz out of the car and put him on the hood, guns drawn. Just then, his friend Rhett drove by — on the wrong side of the road — and took out a fence right in front of the cops. They were so busy with Scuzz, they didn’t even notice. Eventually, they figured out that Scuzz didn’t have a gun and let him go. Later, when he got home, he realized that he had twenty grand in his pocket. He had no idea how it got there. “Someone at the party,” he says, “must have owed me money or something.”

The next night, they had another party at the same house.

By this point, the operation had expanded to include at least thirty-two people. They were making four to six runs a month, moving hundreds of pounds of B.C. Bud to California, Montana and other parts of Idaho.

Topher, though, was becoming anxious. He’d already tried to quit once, but Nate had upped his pay to $8,000 a run. “So I kept doing it,” he says. “But I told myself, ‘This is going to have a horrible ending.'” He tried to warn his friend about being so flashy with his spending, but Nate just laughed, insisting he wouldn’t stop until he went to prison.

The Coeur D’Alene police department knew about Nate and his crew, but the cops were too busy to bother with pot dealers. “They were back-burner cases,” says Detective Morgan. “We were doing three meth labs a week. We don’t hold a back seat to anybody with our meth labs.”

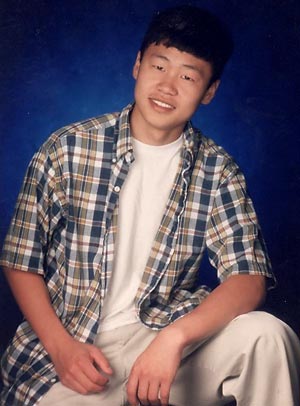

In the end, Nate was not undone by his own greed but by overlooking one of the basic tenets of capitalism: Never underestimate the competition. Nate’s most serious rival was a kid named Brendan Butler. Born in Korea, Butler had been adopted at age two by an upper-middle-class couple in Hayden Lake, a suburb of Coeur D’Alene. His friends and family all called him by his nickname, “Wang,” which means “little prince” in Korean. Butler was a short kid, only five-foot-four, but exceptionally bright, having graduated early, and with honors, from the prestigious Gonzaga Preparatory School in Spokane.

Instead of going to college, though, Butler had an epiphany similar to Nate’s. Soon after graduation, he’d set up his own smuggling operation. And like Nate, he wasted no time in working up his own gangster persona. He drove around town in a low-riding ’93 El Dorado with tinted windows and tricked-out rims, and began abusing cocaine and OxyContin.

In a market as small as Coeur D’Alene, there was bound to be trouble. Nate and Butler “were running across a lot of the same customers,” says Detective Morgan. The crews clashed as they encroached on each other’s territories. As Topher says, “It became this ‘fuck you’-‘fuck you‘ situation.”

Butler began to put out word that he was looking for “muscle.” Through friends, he met an older “enforcer” type — a thirty-three-year-old aspiring graphic artist with no criminal record named Giovanni Mendiola, Gio to friends. Butler met with Mendiola in Coeur D’Alene and told him that he wanted Nate and Scuzz robbed and killed. Mendiola agreed to do the job for $100,000. A few days later, Mendiola checked into a Howard Johnson’s with his brother Eddie and two other men. Butler paid them $5,000 upfront, then accompanied them on a shopping trip to Kmart, where they bought black shoes, pants, gloves and windbreakers, as well as tarps for disposing of the bodies. Butler also provided guns: two assault rifles, a .357 Magnum, a 9 mm semiautomatic pistol and a Tech 9 handgun. Mendiola had brought his own knife. He planned to cut off Nate’s and Scuzz’s fingers.

One night in June 2002, while Butler hosted a big “alibi party” so he couldn’t be implicated, Mendiola and his crew broke into Scuzz’s house. Scuzz and his girlfriend, Crystal Stone, didn’t hear anything until a group of armed men with shaved heads and goatees kicked open their bedroom door and began yelling in a combination of English and Spanish. Crystal, who was nude, was bound with white plastic zip ties and gagged with tape, while Scuzz was forced to reveal the location of his drugs and cash. After robbing Scuzz, the men let him go. Returning to Spokane, they divided the spoils with Butler and made plans to return later to finish the job.

Nate’s crew, meanwhile, was rattled. Nobody knew what to make of the robbery, which only added to the overall paranoia. “We didn’t know it was Butler,” says Topher. “We thought it must be some dudes from out of town. All kinds of rumors were going around.” The day after the robbery, Scuzz moved, and he began sleeping with a Tech 9 under his pillow.

Later that summer, Nate broke both of his arms in a dirt-bike accident and moved in with Buffy. “That was a bad time,” she recalls. “Nate’s arms were in casts. I was recovering from my surgery.” She fluffs her breasts as a visual aid. “And my cat Titty Bar Bob had broken his back, and he got addicted to these painkillers. He’d crawl up the sides of the wall to get to them. It was a weird summer.”

Back in Spokane, Mendiola was growing angry with his client. Butler had yet to pay the agreed-upon advance and kept providing bad information. He insisted that Scuzz had not moved (when a simple surveillance run quickly proved otherwise) and gave Mendiola a crude drawing of a house that was supposed to be Nate’s.

Nobody knows for certain what happened on October 11th, when Mendiola and his men met Butler at a campground near Hayden Lake. Butler planned to show the men a remote location to dispose of the bodies. But at some point, his contrived “gangsta” persona apparently rubbed this group of actual gangsters the wrong way. In what police describe as a dispute over money, Mendiola turned on Butler. As his brother and friends watched, shocked, he began choking the undersized twenty-year-old, who begged for mercy. Mendiola continued choking him until blood came out of his mouth and nose. After Butler was dead, Mendiola slashed his throat repeatedly with his knife, hoping to cover any fingerprints. Leaving Butler’s body in the woods, the men proceeded to one of his safe houses and stole sixty pounds of marijuana.

A month later, a woodcutter discovered Butler’s body. “Once they found the body,” says Detective Morgan, “it was like, ‘Holy shit. It’s not just kids out here smoking dope and buying Escalades and boats. There’s a dead guy out here.'” Investigators quickly tracked down Mendiola, after discovering his number in Butler’s cell phone; the crew was arrested in March 2003. Police also began running surveillance on Nate’s crew.

After news of the murder broke, Nate and his guys were shaken. “Everybody started pointing fingers at everybody else,” says Topher. Things, suddenly, had become far heavier than anyone had anticipated. It was also clear that a body would bring more heat to the scene, so they began to make plans to dissolve the operation and either retire or leave town.

“It was like, ‘This dude Butler is done, we made all this money; now we either need to take a break or get out of it completely,'” Scuzz recalls. “Nate had a house rented in San Diego. It was like one of those houses on — what’s that fucking show? The Real World. Nine bedrooms. An indoor swimming pool. It was sick.”

The group assembled at Tim Hunt’s house early one morning in April 2003, with plans to hit the road by 6 a.m. “We all met on time, but we didn’t leave on time,” says Scuzz. “This guy’s not packed yet. This guy needs to put his street bikes away. If we had left on time, I don’t know what would have happened. Instead, we were sitting around like a bunch of stoners, and we weren’t ready to leave until nine. And that’s when the raid happened.”

Hunt’s house was one of the sites under surveillance. When police spotted a U-Haul, they decided to strike, seizing guns, cash, marijuana and computers. Morgan spent the rest of his summer turning informants and building a case against the crew. In November, his department, working in conjunction with the FBI, made fourteen arrests, including Scuzz, Topher, Hunt, Rhett Mayer and Buffy. The crew was accused of moving at least seven tons of B.C. Bud, worth $38 million.

Nate, who remained at large, decided to surrender himself to the authorities. For legal representation, he hired Frank Cikutovich, whose e-mail address begins with the letters “FU DEA” and whose business card folds open to reveal a stack of rolling papers. Cikutovich recalls the reaction when he accompanied his client to the police station. “In their mind, it’s like they’ve just caught Noriega,” he says. “And here’s Nate, all five feet of him, in his Izod shirt, looking like his mommy bought it for him. It was like Geraldo Rivera opening the vault. Like, ‘Is that it?’ This is the guy who’s orchestrated a multimillion-dollar operation? And he looks like, and has the job skills of, a pizza delivery boy?”

Nate had promised his friends that he would cover their legal fees if anything went down. But once they were busted, the guys wasted no time rolling over. “Everyone told on everyone,” Scuzz says. “If they tell you you’re getting ten years, it’s like, ‘Fuck that. I’m eighteen years old.'”

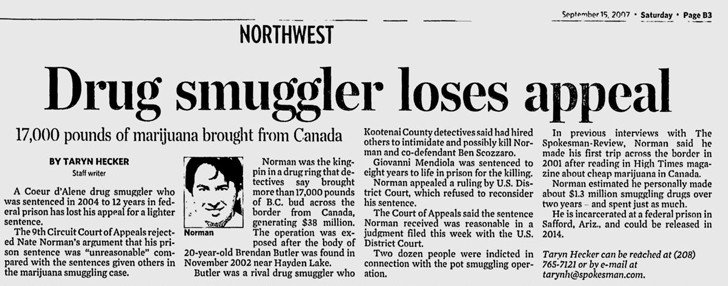

When the cases went to trial in 2004, Nate was portrayed as the kingpin of a drug empire. Scuzz and Topher both got thirty months; most of the others, somewhere between thirty and forty-six. Nate pleaded guilty to five of the fifty-nine counts against him and received a twelve-year sentence; ten years of the sentence is a mandatory minimum and not subject to parole. Giovanni Mendiola, by contrast, pleaded guilty to the murder of Brendan Butler and received a life sentence with a possibility of parole in eight years.

Nate, currently appealing his sentence, has declined all interview requests. Just before he went to prison, he spoke briefly with a reporter from the Spokesman-Review in Spokane, insisting, “I’m no kingpin. I never told anybody what to do.” The writer described Nate as smiling and waving from the other side of the jail’s bulletproof glass, possessing “the eager grin and jazzed body language of someone who had just had an excellent adventure.”

Buffy was convicted of possession and is currently on parole. As part of her sentence, the judge ordered her to wear a key around her neck — “the key to your future” — as a reminder to keep straight. Buffy bought four keys: one gold, one white gold, one Playboy bunny and one white gold with diamonds. She has kept a scrap album of newspaper clippings from the trial, complete with word- and thought-balloon stickers that comment on what happened. On the day of her arrest, for example, her mug shot is thinking, “This must be my lucky day!” Next to the POT SMUGGLER GETS 12 YEARS headline, another balloon reads, simply, “Mr. Right.”

Still, Buffy and Nate remain a couple. They talk once a month. Buffy, these days, mostly strips to “missing you” songs, like Simple Plan’s “Miss You” and — her favorite — Pink Floyd’s “Wish You Were Here.”

Scuzz, meanwhile, avoided prison by going to boot camp; he’s currently serving his time in a halfway house in Long Beach. We meet at a Jack in the Box near the garage where he works six days a week. Through the plate-glass windows, dun-colored mountains are visible in the desert haze. Scuzz hates the halfway house and his job. But he’s still with his girlfriend, Crystal, whom he describes as a “down-ass chick,” adding, “I almost got her killed, and she’s still with me.

“It’s funny,” he continues. “Everyone asks me, ‘Do you regret what you did?’ And the answer is, fuck no. I mean, I think of myself as an entrepreneur, and I went about some of that the wrong way. But I’ve done more at twenty-two than most people do their whole lives. I partied my ass off. There were so many women. I smoked so much weed. Anyone says they regret that, they’re full of shit. They’re saying that to please other people. I don’t care. I had a blast.”

(Posted oct. 06, 2005)

By MARK BINELLI

rollingstone.com

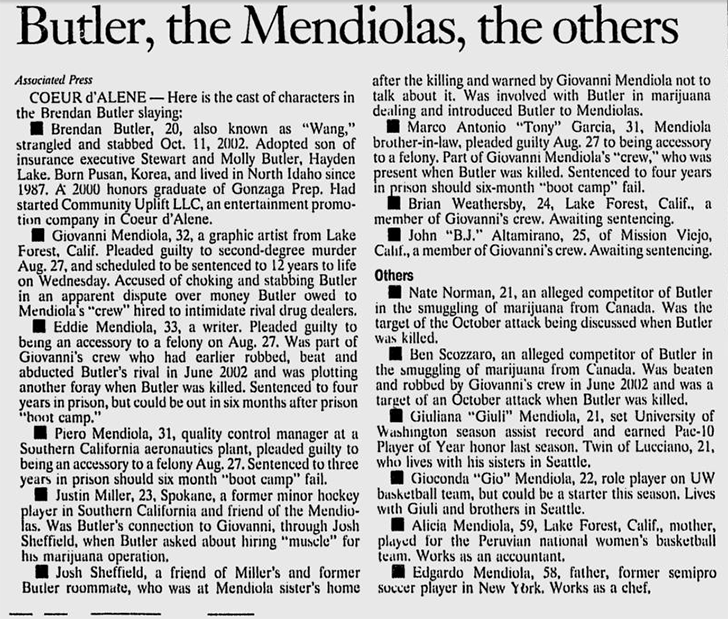

Aftermath arrests

Nate Norman is a FREE MAN!

Nathaniel Nate Norman known as kid cannabis is a FREE man as of December 10th 2013. This photo was taken by his parents when he came out of prison and was treated to Starbucks.

Nate Norman recent prison photo taken. #13023-023 is expected to be released 06-09-2014

Kid Cannabis the movie directed by John Stockwell

John Stockwell (“Into the Blue,” “Blue Crush”) will adapt and direct “Kid Cannabis,” based on the real-life story of young Idaho suburbanites who built a multimillion-dollar marijuana ring reports Variety.

John Stockwell (“Into the Blue,” “Blue Crush”) will adapt and direct “Kid Cannabis,” based on the real-life story of young Idaho suburbanites who built a multimillion-dollar marijuana ring reports Variety.

Stockwell optioned several articles about the illicit ring, including the 2005 Rolling Stone piece “Kid Cannabis: How a Chubby Pizza-Delivery Boy from Idaho Became a Drug Kingpin” by contributing editor Mark Binelli.

Binelli’s article focused on Nate Norman, a 19-year-old from Coeur D’Alene who ran the operation with six friends. By the time they got arrested, they had sold $38 million worth of marijuana smuggled from British Columbia.

Stockwell, who is penning the script, will rely on Kevin Taylor’s article “Dreaming in Green”.

Inside look of Kid Cannabis movie set on ET Canada with Jonathan Daniel Brown

An eighteen year old high school drop out and his twenty-seven year old friend start trafficking marijuana across the border of Canada in order to make money and their lives are changed forever.

Kid Cannabis, the movie, coming 2013?

Dreaming in Green by Kevin Taylor

How much marijuana was sold in America last year? The answer is not a number; it’s a blinding flash of revelation. It’s the sort of brilliant light-bulb burst that led young men – in their late teens and early 20s — in Coeur d’Alene and Spokane on a Fantasy Island journey lined with the pleasant greens of weed, cash and adventure.

How much marijuana was sold in America last year? The answer is not a number; it’s a blinding flash of revelation. It’s the sort of brilliant light-bulb burst that led young men – in their late teens and early 20s — in Coeur d’Alene and Spokane on a Fantasy Island journey lined with the pleasant greens of weed, cash and adventure.

It has revealed a much-wanted drug lord around here to be a smiley, cow-licked pizza delivery kid who looks like he’d mow your lawn and help old ladies cross the street. It has revealed that B.C. Bud, originally planted by draft-dodging hippies rebelling against corporate culture, can become just as big a commodity as McDonald’s cheeseburgers and just as about as profitable.

read the full story

Brendan Butler murdered October 2002

A month later, a woodcutter discovered Butler’s body.

“Once they found the body,” says Detective Morgan, “it was like, ‘Holy ****. It’s not just kids out here smoking dope and buying Escalades and boats. There’s a dead guy out here.'”

Investigators quickly tracked down Mendiola, after discovering his number in Butler’s cell phone; the crew was arrested in March 2003. Police also began running surveillance on Nate’s crew.

Read more about Brendan Butler

Topher Clark murdered February 2019

Michael “Topher” Clark – who gained notoriety in the early 2000s for his role in a Canadian marijuana smuggling ring that inspired the film “Kid Cannabis” – has been identified as the victim of Sunday’s fatal shooting in Hayden.

Clark, 45, was shot multiple times after getting into a fight with another man at The Tipsy Pine, a bar at 8166 N. Government Way where he was a regular, according to court records.

Scott M. White, 33, of Coeur d’Alene, was arrested in connection with the shooting. He remained in the Kootenai County Jail on a murder charge Monday with bond set at $1 million.

Sheriff’s deputies responded to the bar at about 1:40 a.m. Sunday and found Clark and other patrons in the parking lot, according to court records. White was being held at gunpoint by one of Clark’s friends.

Read entire story on the Spokesman-Review

Kid Cannabis press archive:

- High times, hot crowd

- Kid Cannabis (2013) – IMDb

- LegalJoint: Frank Cikutovich Article – Suspected Drug Smuggler Surrenders

- Basketball provides an escape for tragedy-ridden Mendiola family

- Giovanni M. Mendiola appeals from the district court’s order denying his application for post-conviction relief

- Mendiola brothers indicted in Idaho man’s death | The Daily

- U.S. keeps man in legal limbo – Los Angeles Times

- Pot smuggler gets 12 years for adventure

- John Stockwell talks about shooting Kid Cannabis

- Behind the Scenes of ‘Kid Cannabis’ – YouTube

- ‘Sons of Anarchy’ Star Ron Perlman Tackles Role as Jewish Drug Smuggler in ‘Kid Cannabis’

- LegalJoint: Frank Cikutovich Article – Man Pleads Guilty to Pot Smuggling Charges

- Pot smugglers get at least 30 months each – Spokesman.com – July 13, 2004

- Judge sentences 3 in marijuana smuggling ring

- Guilty plea entered in Butler case

- Michael ‘Topher’ Clark, ex-pot smuggler who inspired movie ‘Kid Cannabis,’ killed in Hayden shooting

- KidCannabis.com – 5 stars – CannabisWorld.biz